Supervising Mediation Practice Matters

Supervising Mediation Practice Matters

BY TONY WHATLING

Why does the supervision of mediation practice matter? Author and mediator Tony Whatling explains the origins of PPC in this in-depth article. As a founding members of the Professional Practice Standarts Committee he has a keen insight into the historical development of supervision practice.

“Supervision needs to be clearly focused on the real nature of practical coaching and mentoring. Reflectiveness results in mindful work where we constantly consider what to do, why we do it and examine it to see how we can do it better. Supervision is a forum for reflecting on work in the presence of another or others who facilitate that process”.

— Dr Mike Carroll

This article will explore issues related to the supervision of mediation practitioners, some general social perceptions of supervision, trace the historical development of mediation supervision in the UK over some three decades, describe the current predominant model and definition of supervision practice, and conclude with a focus on direct observation of practice.

How did we get to where we are now?

In terms of how supervision, now referred to as ‘Professional Practice Consultation’ (PPC), when recalling the evolution of PPC in UK family mediation practice, I am reminded of the old joke in which a motorist lost in Suffolk is relieved to find a farmer leaning on gate and asks him for directions to Ipswich. Sucking heavily on his piece of straw the farmer replied: “Well now then, if I were going to Ipswich, I wouldn’t start from here”.

Given that the role and function of PPC now occupies a very central position in the practice of family mediation across the UK, it may surprise many of the current generation of practitioners to learn that it was almost two decades after the family mediation arrived at these shores, that training for supervisors became available.

“At this stage in the life cycle of family mediation, there is good reason to be concerned about the danger of incompetence among those who are practicing mediation with inadequate or no training or with little or no understanding of the concepts basic to mediation.” (Grebe, 1988 in Robinson M. & Walker J. 1992)

This quotation was used to introduce a Chapter entitled ‘Training and consultancy in the 1990’s’. The writers went on to say: “A major component of current training is the determination of the acceptable amount of supervised practice and the level of comprehensive evaluation to be undertaken prior to any practitioner being able to be labelled as a conciliator. This will encounter the primary problem of the very different training experienced by the pioneer conciliators who have had to develop training programmes after developing their practice. Not much supervision or consultation was available to this group of conciliators and that was much evidence in the CPU research that conciliators did not take advantage of the consultation that did exist. … Another recommendation, (made by the CPU), reflected the present paucity of regular consultative support for conciliators despite the stressful and demanding nature of the work.” (Robinson M. & Walker J. 1992)

This interesting piece of archive literature needs to be read in the context of the gradual development of mediation provision in the UK.

From the very first service established in Bristol in 1978 there followed a steady increase in similar ‘Family Conciliation’ services across the country, in which a combination of probation officers, marriage guidance counsellors, social workers and lawyers attempted to introduce and develop mediation practice.

The advent of the National Family Conciliation Council (NFCC) in 1983 was followed by the first ever skills based training programme, designed by Lisa Parkinson and funded by a grant from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. The programme was piloted in a selected group of services that had recruited and selected potential trainee mediators. Very soon after delivery of these courses, a small team of trainers (including myself) was appointed by NFCC to review, evaluate, adapt, and to begin delivering programmes throughout the UK.

Coming back to the initial quotation of this section by Grebe, Robinson and Walker, it is hard to imagine today, that throughout these early steps in the development of mediation practice it was some seventeen years, before the need for training mediation practice supervisors was finally addressed and achieved.

In 1995, National Family Mediation (formerly the National Family Conciliation Council) invited tenders for the design and delivery of the first UK supervision training programme and I was appointed. The programme was piloted, evaluated, approved and began to be delivered throughout the UK.

This was followed some three years later by the commissioning of the design and pilot of a ‘post basic’ or ‘advanced level’ programme by two other trainers. This was not well received when evaluated and in 1999 I was given the task of redesign and re-piloting of the programme.

Despite being very positively evaluated by participants, as a three day module, it became regarded as too resource costly for mediators and services, and after a year or two it was shelved.

This slow evolution of practice supervision does not mean that mediation practice was being completely unsupervised up to that point. Indeed, most early ‘not for profit’ services quickly recognised the need for some form of oversight of practice standards.

This consultative role was largely achieved from what could be described as ‘borrowing from the neighbours’ – namely by drawing on the good will of known practice supervisors from other contexts such as social work, counselling, probation, family court welfare and child guidance.

It was to the credit of such colleagues, that alongside the work of the pioneers and early settlers of mediation practice here in the UK, this largely uncharted professional practice territory, was duly explored and mapped.

So from what source was the theory, content and process of that first ever UK supervision training programme drawn?

As head of a university department of social work education I had collaborated with a local authority to develop and deliver a series of post qualifying training courses, including one for social work practice supervisors.

There was a potential risk that this ‘cut and paste’ approach might be challenged as incompatible with the role of a mediator, yet it seemed to be a very transferable process. Such challenges were indeed raised by some mediation colleagues and fellow trainers. This was perhaps not surprising, when one recalls the efforts of pioneers at that time, to differentiate mediation from existing professional contexts such as counselling, therapy and legal advice. It is reassuring that despite such concerns it has become such an endurable, transferable and adaptive model – so I am tempted to quote T. Bert Lance in 1997: “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it”.

The theoretical model in question derives from Kadushin, who defined three key ‘tracks’ that constituted a supervision process, “Administrative, educational, supportive …with the supervisor having responsibility to deliver all three components to the supervisee in the context of a supervisory relationship.” (Kadushin 1985)

Later, Garfat defined a similar model described ‘S.E.T.’ using the format of ‘Support, Education, Training’ and described supervision as “A learning process within the overall framework of enhancing the quality of services delivered…”. (Garfat 1992)

Adapting such concepts to mediation practice, Kadushin’s original three tracks were further defined as follows:

1. Accountability – The expectation that all staff will demonstrate responsibility for the highest possible standards of professional practice and quality assurance.

2. Development – The responsibility to ensure that the mediator obtains the essential knowledge skills & values, and to regularly monitor, evaluate & appraise development towards professional accreditation & further training needs.

3. Support – Recognises the often complex & stressful nature of mediation & the impact on the mediator as a person carrying a range of other demanding professional & personal responsibilities.

To that list were added three ‘basic assumptions’ that with hindsight were probably designed to placate and reassure potential critics who were inclined to challenge the applicability of Kadushin’s model:

1. Common Tasks: There are common tasks for the supervisor in any organisation, however varied the job or context

2. Common Needs: The nature of the work is such that all staff need recognition and support. Staff in helping organisations are regularly faced with much human sadness and distress, are often uncertain about how best to help, and often work with inadequate resources

3. No One Pattern: There is no one pattern of supervision that is correct for every job and context. The functions of supervision can be carried out in day to day contact, in group meetings, individual sessions and in a variety of other methods.

Having had the good fortune of attending a number of workshops by the late John Haynes, I was also attracted to his process model, which as far as I am aware was never published, and which I came to describe as the ‘reflective pathways model’.

John described the familiar staged process by which a mediator asks questions of the parties so as to uncover their Issues, options and potential agreements.

This format he illustrated diagrammatically as follows:

John went on propose that in a supervision session, the PPC would use very similar questions, but once the supervisee had outlined the client’s circumstances, it was important for the PPC to switch her/his line of enquiry to focus on the supervisee – illustrated as follows:

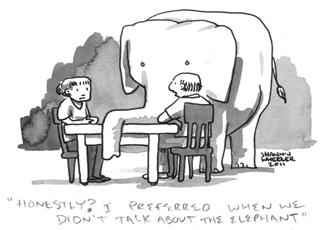

This simple but illuminative diagram illustrates so clearly how, once the basic facts are recounted by the mediator, the PPC must consciously move the focus of issues, options and agreements discourse from clients to mediator. There needs to be a clear understanding of this concept. Otherwise, since by definition PPC’s are also mediators, it can be tempting to continue discussing the clients, their issues, history, and behaviours etc, as it were in some quasi peer professional practitioner chat. This conceptual error was certainly common in the early days of supervision, and may still be characteristic of some PPC sessions to this day. Clients after all are so much easier and more interesting to talk about than what may be potentially more contentious standards of mediator performance – elephant – what elephant?

Inspired by such concepts and diagrams prompted me to create another diagram, (see below with special thanks to Lee Williams for the graphics), that conceives of PPC as three constellations, each illustrating the three key elements of the activity. The three overlapping zones, A/D, A/S and D/S represent the interface between any two particular functions. It helps to imagine that each circle is pinned to a surface but with the pin not in the centre, so that as each revolves, so the total area of focus shifts. When that happens with two of the interface zones, the third is diminished. An anecdotal example involved a competent and experienced supervisee, who brought to a session the fact that they were currently involved in their own marital separation. The mediator felt that it was important to let me know this and, that whilst being under considerable personal stress, they nevertheless wanted to continue with mediation practice. They were nevertheless concerned about the extent to which they could maintain their professional role and objectivity and were asking for help with monitoring that risk. Another example involved a mediator who, having been a former victim of domestic abuse, was requesting a direct observation of her practice, so as to monitor the extent to which this may affect her impartiality. The integrity and professionalism of these practitioners stands as an impressive testament to their professionalism.

Returning to the constellations diagram it can be seen that such conversations as referred to above, and subsequent monitoring of practice, would expand one of the three overlapping zones, namely A/S and therefore, temporarily diminish A/D and D/S. In other words, whilst a sympathetic and empathic PPC might be inclined to move into support mode, they must nevertheless retain role responsibility for the accountability function. It can be seen from this example that no one PPC session is likely to embrace all three ADS foci. It may be that activity in any one of the overlap zones may be required over a number of sessions. Nevertheless, it would be expected that over the course perhaps of a year of PPC, all three dimensions of ADS will be receiving some attention.

Wither Professional Practice Consultation as a title?

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” (Shakespeare, Romeo & Juliet).

So how did mediation supervisors come to be redefined as PPCs?

The creation of the then ‘UK College of Family Mediators’ (UKCFM), now the ‘College of Mediators’ (COM), in 1996 gave rise to a very substantial workload for the Professional Standards Sub-committee (PSC) in creating professional codes of practice such as mediation standards for training and practice etc. Inevitably, the matter of monitoring practice standards via supervision, ultimately also resulting in a code of practice (2000, 2003). As one of the lead bodies involved in creating the UKCFM, NFM representatives were able to bring to the table the aforementioned work on supervision standards, models and training. Early discussions on this topic in the PSC were characterised by concerns, particularly from the lawyer mediator representatives, as to the necessity for professional mediators to have their practice monitored by a supervisor. Memorably, one such objector referred to the fact that he has been appointed to his post as a lawyer, on the basis that he would be “capable of practicing without supervision”. A parallel resistance from the lawyer mediator group in particular, that lingers on to this day, was an attempt to seek to detach a supervisor from any direct accountability for the practice of those they supervise. Such objectors argued that a supervisor can never actually be in a position to assume accountability for the practice of a fellow professional. From my earliest involvement in efforts to introduce supervision into social work practice in the early 1970’s, such social perceptions and reactions were very familiar.

Without doubt, the notion of supervision was commonly perceived as a process whereby an ‘overseer’, as it were, observed your work so as to tell you what you were doing wrong and where you fell short of a required standard.

For many professionals, it was also associated with passing or failing as a student, for entry or blockage into their chosen profession, e.g medicine, law or teaching. For the latter, the experience of direct classroom observation and assessment of trainee teachers had been such an ordeal as to cause shivers down the spine for many years to come.

It was clear that attempting to introduce supervision in terms of the potential benefits, not just for clients, but also for constructive on-going development and support, required a capacity to work respectfully with such deeply embedded cultural perceptions and resistances.

For a number of PSC meetings that attempted to formulate a code of practice on supervision, such resistances constantly re-surfaced. This issue subsequently resulted in a significant split between representatives, broadly speaking from social sciences backgrounds on the one hand, and legal practitioners on the other.

To its credit, the PSC took the decision to hold a half-day workshop on issues relating to the monitoring and oversight of professional standards designed to protect consumers of mediation. My personal position throughout the debate was, that as professionals in the field of dispute resolution we invited clients to come to us for help. As such, mediation was inevitably and inescapably by definition, a ‘publicly accountable activity’ and therefore, its practitioners must be adequately supervised.

Since it seemed that the very term ‘supervision’ invoked such a negative reaction, I cared little for what label we were to come to adopt, provided that the definition of the role included the three key elements referred to above, i.e. ‘Accountability, development and support’.

In the best traditions of such debate we duly separated into a number of mixed professional sub-groups tasked with addressing the key issues, and reporting back via the traditional flip-charted opinions.

Surprisingly, in light of the former disagreements it was the lawyer mediator representatives that were most vocal about the need to protect the public from unsatisfactory standards of practice by poorly trained or untrained mediators.

It seemed ironic that those who had hitherto raised such objections and resistance to the notion of supervised practice, were now the most strident in calling for some form of practitioner oversight.

“All’s well that ends well.”’ (Shakespeare)

After further group debate and a search for an alternative to the negative constructs associated with supervision, it was finally agreed that Professional Practice Consultation (PPC), would be acceptable. What mattered more than the label was that it was also agreed that the definition of PPC would embrace the three key elements, Accountability, Development and Support.

The PSC went on to elaborate on this basic framework as follows:

Accountability:

To help safeguard clients through monitoring practice.

To induct new mediators into the mediation profession.

To help monitor standards for the Agency and the national body.

To challenge unethical practice.

Development:

To support and help promote competent practice.

To train and promote development of new mediators.

To coach and encourage new ideas and practice.

To reflect back and encourage the development of the reflective process and of the internal supervisor.

To provide fresh perspectives.

Support:

To encourage confidence.

To allow vulnerability to be aired.

To allow frustration or distress to be aired.

To permit off-loading from within the work context and outside it, where appropriate.

Direct evidence versus hearsay – Direct observation of practice matters – PPC’s do it with ‘super-vision’.

“And would some Power the small gift give us

To see ourselves as others see us!

It would from many a blunder free us,”

— Robert Burns 1786

Finally I want to raise the question of the direct observation of practice in PPC.

“Direct observation of practice by the supervisor or professional practice consultant (PPC), while not a requirement of the Quality Mark Standard for Mediation, is considered to be: a particularly valuable means of fulfilling the quality control function of the supervisor. It shows how the mediator manages the mediation session and allows the quality of management to be assessed…. Direct observation is a simple and effective way of demonstrating and recording the quality of practice independently and objectivel.” (Legal Services Commission, 2002 in Roberts M. 2014)

Observed practice is not new, indeed for some professionals, who perhaps like Burns, wish for the power to see themselves as others see them, it has become familiar practice. Nevertheless it remains a contentious issue for many practitioners who continue to look for various reasons and excuses to avoid it.

By ‘observed practice’ I am referring to a process whereby the PPC, or other designated colleague, directly observes the practice of the mediator. For a more detailed account of the potential process, methods, pros and con’s and a suggested recording format see Whatling (2013).

Objections frequently focus on the problems it will cause for the client, usually accompanied by the disclaimer, ‘not that it is a problem for me as a mediator of course’! Whilst there will be elements of reality in such objections, it seems clear that it is usually far more of a problem for the practitioner than for the client. Yes the session dynamics may be affected, but why assume that it will be for the worst?

All such objections need to be weighed against the very real benefits for professionals and ultimately for their clients. Mediators are good problem solvers, so most of the practical and resource arguments are resolvable, assuming of course that the ‘spirit is willing’.

On the issue of time resources, since current PPC contact time requirements call for a minimum number of face-to-face hours per year, live observation offers a very productive use of such time. The immediate post observation de-briefing time can take as little as 30 minutes with the option of any additional analysis/discussion being postponed to the next scheduled PPC session.

Given that mediation is arguably more craft than science, practice is rarely about ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ as such but what is more, or less effective.

A PPC should be primarily concerned with what the practitioner does that is effective and, what could possibly be further developed or done differently/more of or less of.

In the words of Rabbi Lionel Blue, (Radio 4 ‘Thought for the day’), – “Our successes make us skilful, our mistakes makes us wise.”

Examples of weak/poor practice are unlikely to come to light without direct observation. So as Burns so eloquently put it, ‘It would from many a blunder free us! It should be acknowledged of course that mediation is inevitably easier to do as an observer than when sitting in the mediator chair!

Finally, if none of the above arguments in favour of direct observation of practice has convinced the reader, we can consider it from perspective of the quality of hearsay evidence versus witness evidence. “In other words, hearsay is evidence of a statement that was made other than by a witness …..that is offered to prove the truth of the matter stated.” Sourced via Google at ‘Find Law’ 29/10/2014). Such a formal and legalistic terminology may seem inappropriate to use here. However, it is useful to consider the difference between the qualities of feedback an observing PPC can give to a practitioner immediately the session ends, compared to that of an unobserved mediator, describing what had happened some days or weeks later.

This is not to imply that such a practitioner will deliberately withhold data, or seek to obscure any faults or evidence of weak/poor practice. It has more to do with the nature of retrospective discourse, of a typical PPC session. In other words, generally speaking, practitioners tend not to refer explicitly to particular skills or strategic interventions that they used to impact positively on the process and progress of a session other than in fairly general references – e.g “It was had to work hard to maintain constructive communication because of the high level of conflict between the parties”.

Anecdotal experience of using direct observation also suggest that immediate post-session analysis/feedback is often characterised by a self-effacing low self image perception about what happened during the session – e.g. “That was awful, I made a complete fist of that, it was hopeless”. That is not to suggest that this reaction is based on an ego-centric wish for reassurance, nor an attempt to moderate the feedback from the PPC. More commonly it is rooted in a genuine lack of practitioner self-confidence, not least after what may well have been an extremely complex, highly emotional, conflicted and challenging mediation session.

From my experience, it is rare that my perception of the mediator’s performance equals their own negative perception. What is so rewarding about direct observation is that the observer is commonly in a position to disagree with the practitioners self-doubt. Such reassurance derives not simply from a position of wanting to comfort or reassure, by some sort of empathic generalised statement. Rather it comes from much more objective, and documented notes as to the what, how and when, of observed skills, effective strategies and interventions. In other words the PPC can focus specifically on observed/witness evidence that is not based on hearsay. Even where things did not go well and, for example a walk-out occurred, it is still much more effective and constructive to be in position to identify how and when the practitioner may have missed the typical signals that may have predicted the event. Subsequent discussion can then focus specifically on what other options the mediator(s) may have tried, and to reach agreement as to what they will do differently, with a similar session in future, (see above for the ‘reflective pathways’ model).

A few years ago I presented a workshop on direct observation to a Regional PPC group. The concept, process and arguments in favour was well received by that group and yet a quick show of hands poll a about a year later showed that hardly anyone had incorporated it into their practice.

Given all of the above arguments in favour of direst observation of practice, why might it be that it has continued to be avoided by so many practitioners?

One possible account could perhaps be the ‘alligator’ syndrome.

“When you are up to your neck in alligators, it’s hard to remember the original objective was to drain the swamp.” (Adage, unattributed)

In other words when, after years of attempting to stay afloat at times of consistent under-funding of mediation in the UK, the alligator adage may apply for practitioners, who find it difficult to incorporate professionally innovative ideas and methods.

Secondly, it may also have to do with the aforementioned conscious or sub-conscious resistances to exposing oneself to the direct scrutiny of a professional colleague.

Thirdly it may also be rooted in concerns of PPC’s as to their competence to undertake such an immediate assessment function. Anecdotal experience as a CPD trainer suggests that whilst many PPC’s perform intuitively as mediators at a very competent level, they are nevertheless often unable to name and define the specific skills and strategies they use. In the words of Donald Schon “I begin with that assumption that competent practitioners usually know more than they can say. They inhabit a kind of knowing-in-practice, most of which is tacit.” (Schon 1983).

And a final word from Barack Obama: “What Washington needs is adult supervision”.

Addendum added Jan 2023

Throughout the above text, reference has often been made to family, separation and divorce mediation, not least since that is where the roots of PPC in the UK are located. However, it should be noted that the same practice principles apply to all mediation contexts and are hopefully transferable across all contexts. The development of the College of Mediators with its now inclusive expansion to include all dispute contexts and ever-increasing practitioner membership, has played a major part in that evolution.

References

Garfat, T. (1992) ‘SET: A Framework for Supervision in Child and Youth Care’ The Child and Youth Care Administrator 4 (1) 2-13.

Roberts, M. (2014) ‘Legal Services Commission, 2002. p.155. D4.2’ (Aldershot: Wildwood House)

Robinson, M. & Walker, J. (1992) ‘Training and Consultancy in Conciliation’ in Family Conciliation within the UK Policy and Practice 2nd edition edited by Thelma Fisher Chapter 19. Family Law, (Jordon & Sons Ltd).

Kadushin, A. (1985) Supervision in Social Work (Columbia University Press)

Schon, D.A. ‘The Reflective Practitioner, How Professionals Think in Action’, [p viii], (basic Books 1983)

Whatling, T. (2013) ‘Observed Practice Matters The use of direct observation of mediator practice by the Professional Practice Consultant.’ (College of Mediators Newsletter Issue 12 Dec 2013. and The Indian Arbitrator Vol. 5 Issue 11. Nov. 2013.

Originally published in College of Mediators Newsletter February 2015. Subsequently republished in edited form as Chapter 2 in ‘Mediation and Dispute Resolution. Contemporary Issues and Developments’ Whatling 2021 Jessica Kingsley.

Tony has over 30 years experience as a family mediator, consultant and trainer, with a professional practice background in Social Work in Child Care, Adult Mental Health, Family Therapy, Area Team Management and Social Work Education. Prior to becoming self-employed 20 years ago he was for ten years Head of Faculty at Ruskin Anglia University Cambridge.

He has trained hundreds of mediators throughout UK in Family, Community/neighbourhood, Health Care Complaints, Victim Offender and Workplace mediation contexts. He was an elected Governor of the College of Mediators (UK) and is a founder member of the College’s Professional Practice Standards committee.